Getting Bach in Shape: Left Hand

In a particularly prickly passage from “Playing the Viola: Conversations with William Primrose,” David Dalton asks the great Scottish viola virtuoso William Primrose his opinion on whether violists should play the Bach Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin. Primrose’s answer is characteristically blunt:

“…it is unfortunate that violists too often play these works for violin. There are violists who insist on playing them, and as a rule it is a disaster. Maybe I have been very unlucky in my experience, but I have heard plenty of violists attempt them with appalling results, particularly in the polyphonic movements…The devices students and teachers have to resort to in order to overcome these difficulties are usually very unfortunate—that is, unfortunate to the ear of anyone in hearing range.”

Ouch!

So let’s get this out of the way: Hi, my name is Travis, and I am one of those poor souls that insist on playing the polyphonic movements of Bach’s Sonatas and Partitas on the viola. Here follows some of the unfortunate devices I’ve resorted to in order to play them (hopefully without disaster).

Preludio

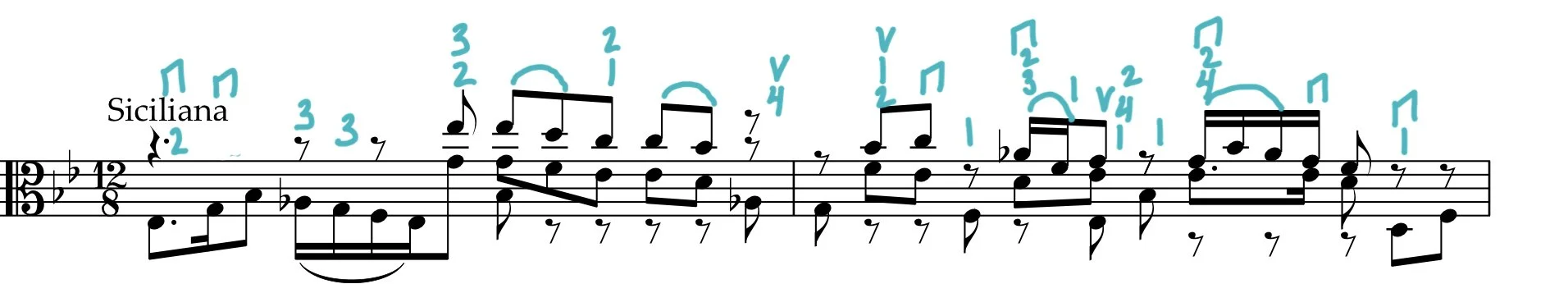

This summer has been back to back Bach for me! I ran my own String Gym Course on the 3rd Bach Cello Suite, and participated in violinist Nathan Cole’s Summer Bach Retreat. Open to both violinists and violists, Nathan’s course covered three of the unaccompanied works for violin — the G minor Sonata, and the D minor and E major Partitas. I’ve done two of Nathan’s previous summer courses and loved them. l knew that my summer was busy enough that there was no way I could get through all of those pieces in the given time frame, so I chose to focus on a few movements — the Loure from the E major Partita, the Adagio, Fugue and Siciliana from the G minor Sonata, and the Sarabande from the D minor Partita.

Before working on these pieces I THOUGHT I had a decent left hand. I’m lucky to have fairly long fingers, so everything was “within reach,” at least theoretically! For years I’ve practiced scales in double stops, and I’ve studied many of the standard left hand etudes: Schradieck, Korgueff, Sevcik etc. I’ve even “played” several of the Paganini caprices on viola! But none of those prepared me for Bach’s knotty contrapuntal writing — it exposed SO many weaknesses in my left hand! Granted, there are just as many challenges for the bow in this music, but for me at least, it was clear my left hand was the weaker half.

I love this music too much to give up without a fight, though, so over the summer I developed a variety of left hand exercises to shore up my particular weaknesses, complementing the excellent instruction in Nathan’s course. In this article (and at least one more!) I’ll discuss some of my specific challenges and the exercises I wrote to address them.

Interval Extravaganza

It’s standard to practice scales in double stops, most commonly 3rds, 6ths and 8ves. But those scales have limited value in the Sonatas and Partitas — different KINDS of double stops come fast and furious in this music, and you’re lucky if you get the same interval twice in a row!

Take this three bar example from the Fugue from the 1st Sonata.

(All musical examples are taken from Nathan Cole’s excellent Urtext edition of the Sonatas and Partitas)

Counting the intervals in the triple and quadruple stops, the only intervals we DON’T play are a minor 2nd, tritone and major 7th. But don’t worry, there are plenty of those later in the movement! I struggled mightily with passages like this, and yet it’s all in 1st position! How could I struggle to play chords in 1st position??? For me this was perhaps the most frustrating and awe-inspiring aspect of these pieces — most of the difficulties never left 3rd position!

Clearly, fluency in EVERY interval in one key in one position is one necessary skill for success in these works. So I began warming up by taking one pair of strings and playing EVERY double stop in one position in one key. This is SO HELPFUL for setting the hand frame, but equally important for accustoming the ear to less familiar intervals. Familiarity with those intervals is not enough, though; the ability to quickly switch between different kinds of double stops is critical in these works.

Since any pair of fingers is actually responsible for two interval classes (e.g. you need the 1st and 4th fingers to play octaves, but if those fingers switch strings they now play a major 2nd), I organized the intervals according to which pair of fingers plays them.

Note: for maximum impact, all exercises should be practiced in the key(s) of the movement you’re playing.

This relationship of intervals in any pair of fingers is important! If you know you can get two classes of intervals simply by switching strings, it’s like a Buy One, Get One Free sale at the double stop store!

More importantly, this “switcheroo” (hat tip to Nathan for that term) happens from time to time in the Sonatas and Partitas. In the example below, in beats 2 and 3 of measure 2, the 1st and 2nd fingers switch from a Perfect 4th to a Major 6th:

However, annoying thing #2678 (yes, I’m cataloging them) of playing a string instrument is that since the fingerboard is curved, the finger can’t just move straight across — there is a slight adjustment required during the switcheroo. If a finger moves from a lower to a higher string, it has to pull back slightly or it will be sharp, if it moves to from a higher to a lower string it needs to be moved forward slightly or it will be flat.

This needs to be practiced, so I came up with this exercise to focus this problem:

To be practiced in other keys, strings and positions

Another advantage of this work is for hand/finger position. Fingers need a different shape depending on the type of double stop. If the higher finger of a double stop is on the lower string — as in 2nds, 3rds & 4ths — a more upright position is required so the finger doesn't touch the higher string. If the higher finger is on the higher string of the double stop — as in 6ths, 7ths & 8ves — the fingers can rest more on the pads. By moving back and forth between these different kinds of double stops, the hand naturally finds a position that is well balanced to play ANY double stop.

A final example of this finger hopping across strings that really got on my nerves had to do with playing 5ths that moved across strings. I wrote this exercise to focus on that problem:

Beginning in the 2nd bar you could continue using only the 2nd finger up the pattern, or begin in the 3rd bar using your 3rd finger.

Finger Patterns and Double Stops

Many pedagogues — Simon Fischer, George Bornoff, Ivo-Jan van der Werff, Robert Gerle, Heidi Castleman to name a few — extol the benefit of thinking in Finger Patterns (yes, they’re so important I’m capitalizing them!). What is a Finger Pattern? It’s simply the arrangement of whole and half steps that our four fingers play in any given position or key.

Somewhat amazingly, on the violin and viola the vast majority of what we play in tonal music can be covered in just four Finger Patterns! Here’s a chart with the four basic Finger Patterns:

| Pattern Name | Half and Whole Steps | Sample Pitches |

|---|---|---|

| Pattern 1 | 1^2_3_4 | E F G A |

| Pattern 2 | 1_2^3_4 | E F# G A |

| Pattern 3 | 1_2_3^4 | E F# G# A |

| Pattern 4 | 1_2_3_4 | E F# G# A# |

Teachers label these patterns in different ways. I find it most intuitive to label them according to where the half steps lie — so the pattern with a half step between 1 and 2 is called Pattern 1, the one with a half step between 2 and 3 is Pattern 2, half step between 3/4 is Pattern 3 and the pattern with all whole steps is Pattern 4.

Thinking in finger patterns is very helpful for single notes, but when we can visualize and feel all the DOUBLE STOPS in one pattern things get very interesting, as suddenly one Finger Pattern accounts for MANY double stops.

You might say to yourself, “Well since I’m always playing in a key, doesn’t it make more sense to think and practice in keys rather than finger patterns?” Excellent question! IT IS important to think in keys, but a good reason to practice and THINK in finger patterns is that it increases your spatial awareness of the fingerboard — by forcing yourself to think about the intervals in your hand, you sensitize yourself to the physical space between notes. Consciousness of that space is so helpful in tackling Double Stop Intonation Hobgoblins!

Here’s an example of how I began thinking in finger pattern double stops:

The first measure shows the notes of Finger Pattern 2 on the D string, the 2nd measure shows all the notes of that pattern in one cluster (that measure isn’t meant to be played :-). Measures 3 and 4 show the same pattern of half and whole steps on the G string. The second line shows all the possible double stops made by combining the notes from the pattern on the G string and the D string.

As with the double stop exercises in the “Interval Extravaganza” portion of this post, I’ve paired these double stops according to which fingers are playing them. So in measure 6, fingers 1 and 3 play the Major 3rd of E and C — but if you switch the string they’re on, those same fingers also play the minor 7th G and A. Again, awareness that those two fingers play two interval classes serves as a mental shortcut to those double stops.

With enough practice, Finger Patterns begin to feel like “frets” — a shape of the hand that your hand can quickly go to that captures many double stops in handy one mental chunk. When the double stops in these movements can be perceived that way, and your brain and fingers aren’t working so hard to perceive individual notes, the flood of double stops becomes much more manageable!

Moving Forward

While these double stop exercises laid a good foundation for my hand, there were MANY more challenges for the left hand ahead. In my next article I’ll tackle my greatest double stop weaknesses — 4ths, 5ths and tritones — and show how I expanded on the exercises in this article to develop “brains” in each of my fingers so that they could move around independently.

Thanks for reading, and if you’d like the next article straight to your inbox, please subscribe below!