How to Learn a Solo Piece in 7 Days

Dmitri Shostakovich

String Gym 4.0 is open for registration. Click for more info

At the beginning of May I had a concert on the books with Camarada, a great chamber ensemble I’ve been playing with for over a decade. A week before the performance, a text came in: one of the musicians in our group had fractured her finger, and the main piece I was playing on had to be scrapped!

Along with Camarada's Artistic Directors, pianist Dana Burnett and flutist Beth Ross-Buckley, I scrambled to find a replacement piece. The concert featured music by film composers, so the piece needed to fit within that theme. Initially I suggested pieces by Nino Rota and Prokofiev, but these were too difficult to put together with the rehearsal time available. In one of our conversations, I mentioned to Dana that I had a vague recollection that Shostakovich had written film music. Armed with that tiny sliver of information, Dana found a recording of a beautiful arrangement of the Romance from Shostakovich's score toThe Gadfly. It was perfect for the concert: poignant, short and it fit within the theme of the concert.

Now we just had to learn and perform it in a week's time!

Readers of this blog may remember a similar (but more stressful) situation I found myself in last year: I had to learn AND memorize two short pieces in about 36 hours, not to mention dance steps to go with them! With that experience under my belt I was confident I could handle this one, but I still needed a plan!

What follows is my own process for preparing the Romance for a public performance in seven days.

Day 1

Dana and I searched for a digital version of the particular transcription we wanted, but couldn't find one for sale anywhere. I had ordered the physical sheet music to the Romance, but it wouldn't arrive until AFTER the concert. Desperate, I turned to Facebook, sending out a call to my violist friends to see if anyone had a scan of the music. While waiting for an answer, I listened to a few different recordings of the piece.

I like to do my initial listening without sheet music, so I didn't mind that I didn't have it in hand yet. In my first listenings, I write down my impressions of the piece, whatever they may be. These observations are all over the map: sometimes it's an emotional reaction, sometimes it's an image, or maybe it's just a particular part or section that stands out for its interesting harmonies or unusual rhythms.

While they may seem ephemeral, I find these initial impressions to be important: they are the kernel of my personal interpretation! On the one hand, my reactions to a piece will be unique to me, and on the other, these observations help me think about what aspects of the piece I want to highlight for my own audience, who are likely hearing it for the first time as well. Putting myself in the listener's shoes helps me to create more accessible interpretations.

To me, performers are musical tour guides of sorts, drawing attention to the parts we find interesting to our audience ("and on your left you'll find an interesting circle of 5ths sequence..."). Perhaps more importantly, doing this kind of listening prevents me from immediately going into "learn the notes" mode, where I'm just hashing out technical problems without any musical intention.

A common refrain I hear from students is "I have to learn the notes, then I’ll make it musical." This is backwards! Musicality affects your timing, pitch, dynamics, bowing choices etc. If you learn a piece without any of that and just "learn the notes," then you'll have to relearn parts of the piece when you "insert musicality" at the end. This is one powerful reason why having a musical opinion about the piece BEFORE you start, even if you change that opinion, is crucial!

I checked Facebook. An old friend had answered the call and could send me a scan! By the time I received the music it was late in the evening, so no instrumental practice for today.

Day 2

Today was all about getting an overview of the piece and the task I had before me.

I listened to the Romance again on the way to school, then warmed up and ran through it several times. I don't think I'm a great sight-reader, but I AM good at making adjustments each time I play something: run-through two was significantly better than run-through one, and three better than two. After each run-through, I bracketed problem spots, erasing brackets if I could solve the problems on subsequent runs. After all three runs, I was left with a few bracketed sections whose difficulties eluded simply playing through them.

I looked at the measures I had bracketed, searching for patterns. If I could find common technical problems between those sections, I could save lots of time by incorporating exercises focused on those techniques into my daily practice. Honing these parts of my technical vocabulary would also give me the freedom to focus more on music-making and less on technique.

All my brackets involved big shifts, playing high or double stops, so I resolved to include exercises addressing those issues in my daily warm ups (more on that later).

I formed my plan for the rest of the week: I would spend Day 3 polishing the first page, Day 4 polishing the second, then split the rest of my time between performing for people, rehearsing with Dana and drilling persistent problem spots.

Day 3

For a while now I've used a daily practice template introduced to me by Ralph Fielding. Ralph has also been a big influence in how I approach technical practice, so many of the warmups below also owe a big debt to him!

This daily structure is simple and straightforward: if I have an hour to practice, I'll spend 15-20 minutes warming up and doing technical exercises targeted on my repertoire. Next, I'll imagine I'm on stage and perform what I'm working on for an imaginary audience. I record the run-through on my phone, then listen back to the recording and identify the weakest section(s). The rest of the hour is spent working on the those problems spots, periodically recording phrases or measures (I use VoiceMemos on my iPhone) to ensure progress is being made.

With this approach I'm always practicing for performance (to borrow a phrase from another mentor, Nathan Cole), working on my weakest links, rather than wasting time playing parts which are already in good shape. If the piece is hard and I'm early in the learning process, my run-through may be slow, I may play only a section of the piece, or I may simplify or skip over unplayable parts. The point is to perform as if I were on stage, playing as musically as possible.

I spent a good chunk of the day re-fingering the piece. Fingerings are so personal! This violist of this arrangement likes to shift A LOT, frequently choosing higher positions on lower strings for color changes.

I'm a fan of this strategy to a degree, but when playing solo I often can't adequately project my sound with this style of fingering, instead I'll usually choose fingerings in lower positions for their clearer sound.

Day 4

Warmups for today included taking the big shifts from the piece and playing them forwards and backwards, first with separate repeated notes then playing them under a slur. Separate bows encourage a light left hand and keep the shift from being too slow. When practicing with slurs I ensure I'm vibrating on both ends of the shift. Playing shifts forward AND backward helps keep the left hand and arm balanced.

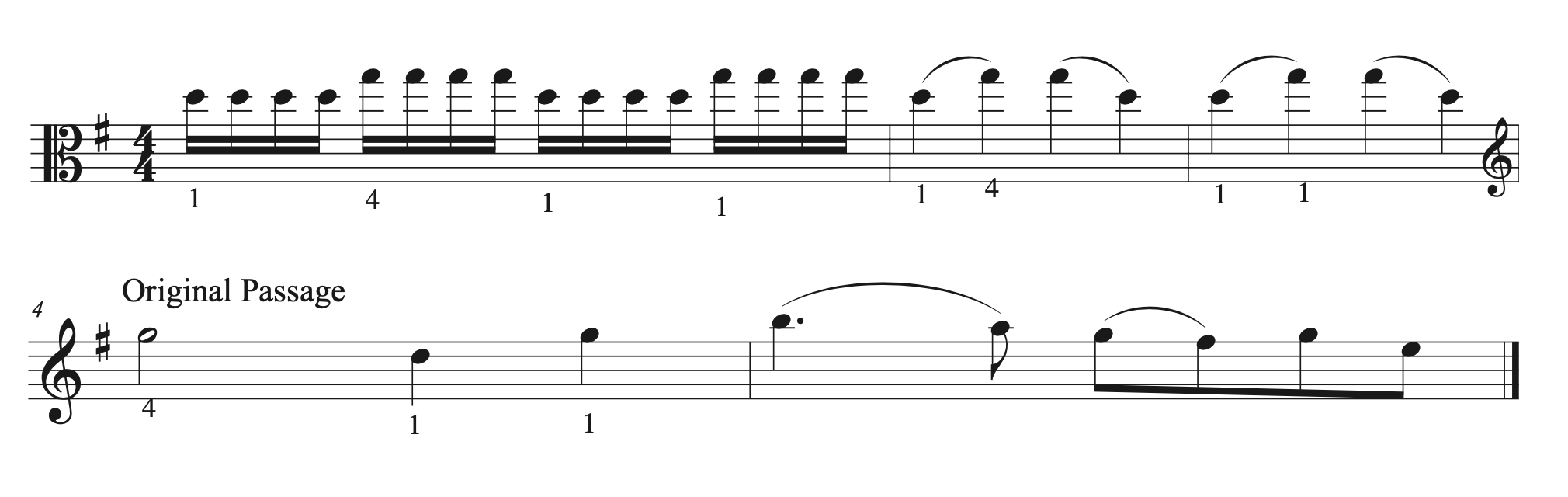

For my double stop warmups, I started by "tuning" my hand in the positions I had to play using hand blocks, another strategy I learned from Ralph. The idea is to play all the double stops in one position in one key. So for a particularly tricky section of double stops on the C/G strings I used this hand block:

I find this practice a great complement to the traditional double stop practice of playing scales in thirds, sixths and octaves, as you can use it to target the particular hand position and key giving you trouble in your piece. The small amount of material also makes it easier to focus on a high quality of sound and intonation for every note.

Hand blocks also cover intervals you might not play in traditional double stop scale practice, like 4ths, 5ths (depending on the piece I'll sometimes throw in 2nds and 7ths!) that show up frequently in the repertoire. With enough practice, one hand block turns into a shortcut to access many double stops!

Day 5

I've always felt that a piece doesn't fully come to life until you play it for someone, and I certainly didn't want the concert to be my first performance! I'm lucky to have San Diego Symphony Principal Bassist Jeremy Kurtz-Harris just a few doors down from me at SDSU. We'll often play for each other when we’re preparing things.

I knew playing for Jeremy would get me a little nervous, exposing which parts of the piece needed more work. More importantly, while I'd been getting regular feedback from my recordings, another pair of ears would shine a light on my musical blind spots.

My play-through was ok: I was able to "play my average," as Burton Kaplan would say. Jeremy's main comment was that he wanted more dramatic musical contrasts in a few specific places. My dynamics, character and color changes in those spots needed to be more extreme to be effective. For example, he wanted a more intense sound in this section, one of the only parts that goes to forte on the C-string:

Responding to Jeremy's request for a more intense sound, I imagined how Roberto Diaz might play the phrase. While I never worked with him directly, I studied Diaz's recording of Primrose transcriptions when I was preparing a recital a few years back, and had listened to it so many times that it was easy for me to imitate his sound and style.

I played the passage again, channeling Diaz. Jeremy loved it! He asked whether it was a left or right hand thing I had changed. I mentioned imitating Diaz, and because we're both pedagogy nerds this sparked a conversation on the benefits of imitating players as a practice tactic.

Jeremy commented on how imitating is a kind of memory chunking—simply by imagining yourself as a player, you can change many aspects of your approach (sound production, vibrato, timing, color etc.) in one fell swoop.

I added that it's also a great way to get out of your own head and expand your range of musical ideas when you feel like you're playing is stale, or in a small musical box. Imagining yourself as another player gives you the freedom to make musical decisions you might be too scared to make when playing as yourself!

I last used this strategy deliberately when preparing Vaughan Williams’s Flos Campi to play with the SDSU Symphony Orchestra. Initially I struggled with what to do musically with the opening melody. Dissatisfied with my interpretation, I started from scratch, imagining how various violists I admire might play it. I spent some time "trying on" versions by Tabea Zimmerman, Ralph Fielding, Paul Coletti, Brian Chen and a few others. Each time I had a clear version of one of those players, I recorded it. After going through all the versions, I listened back to them, determined which one I liked best, and wrote that person's name in the music so I could channel them as I performed.

I decided I needed to channel Diaz for the intense parts of the Romance, and listened to his Primrose album on the way home to get his sound clearer in my ear.

Day 6

Before my rehearsals with Dana I made sure to play through the piece with the recording a few times. I do this with earbuds and my practice mute on so I can hear the recording clearly. I do this practice partially to hear my part within the context of the piece as a whole, but mostly to save rehearsal time: if I HAVEN'T done this during the first rehearsal I get so distracted by the piano part that I don't have the mental bandwidth to focus on my own playing!

Even if the interpretation in the recording is vastly different than my own, playing through the piece with the recording ensures I know what's happening during rests, gets me used to tricky transitions and ensures I'm not locked into playing everything in a tempo that happens to be convenient for me. This work also exposes technical issues that aren't locked in—if there are sections where I have to focus completely on my own part to be successful, then I know they need more work! All of this preparation saves valuable rehearsal time that can be better used discussing the finer points of interpretation.

At the rehearsal, Dana and I ran through the piece a few times, discussing issues of tempo, timing and dynamics. I recorded our last run and reviewed it later in the day, noting what I wanted to improve for our next rehearsal. This is another benefit of recording: it frees me to just PLAY, rather than trying to spend part of my brain noting what went wrong WHILE playing.

Day 7

Performance day! Even though I had little time to prepare, I felt ok, mostly because I trusted that I had prepared in a way that covered as many bases as I could in the short time I had to learn it. Was it my absolute best playing? Not by a long shot! I certainly would have benefitted from having more time for things to settle in, but given my time constraints I was reasonably satisfied with how things turned out. You can watch the recording of it below: