Harmonics and Ponticello: A Partially Perfect Pair

Pat your head with your left hand and rub your belly with your right.

Notice how hard or soft you're patting/rubbing, then try patting your head a bit harder, but rub your tummy with the original pressure. More difficult?

This time, notice how fast or slow you're patting and rubbing, then try rubbing your stomach at a faster speed while your patting hand stays at its original tempo.

Assuming you haven't cut your fingers on your washboard abs, try switching hands!

How was that? Did it take you a minute to get your hands going, or was it easy for you to get them NSYNC?

With this simple exercise, you've elegantly (or perhaps inelegantly) summarized many of the coordination problems that plague string playing. When fingering and bowing, our hands WANT to do the same thing in the same way they wanted to pat your head, or rub your belly, but resist doing both simultaneously, then positively howl when we try to get them to operate with different pressures, or at different speeds.

On our instrument this problem manifests in several ways. When playing forte, for example, we must apply more pressure with the bow, but while applying said weight with the right arm and hand, more often than not the fingers of our left hand press harder into the string. This in spite of the fact that the amount of pressure needed to stop the string while playing forte is only fractionally greater than when playing soft! A waste of energy to be sure, but, more insidiously, this increasing tension in our left hand slows our fingers down, making it harder to play!

Our hands are codependent, and we need them to be independent. Our hands need to spend time apart, figuring out their individual identities, discovering their taste in books and movies, getting their own Instagram's, paying their own taxes, etc. etc. Once they've spent time alone we can bring them together again and reforge a healthier relationship.

But how to do that? To get a Händel on this in my own playing, I've found practicing harmonics and ponticello to be a great technical superset. (In exercise parlance, a superset is a pair of exercises you perform back to back, usually on complementary muscles.). Harmonics are a great way to develop a lighter left hand, as they require the left hand to be light while the bow plays into the string. Ponticello, trains the same skill set in the bow arm.

Let's get started with harmonics.

Harmonics - A Technique I’m HIghly PArtial To

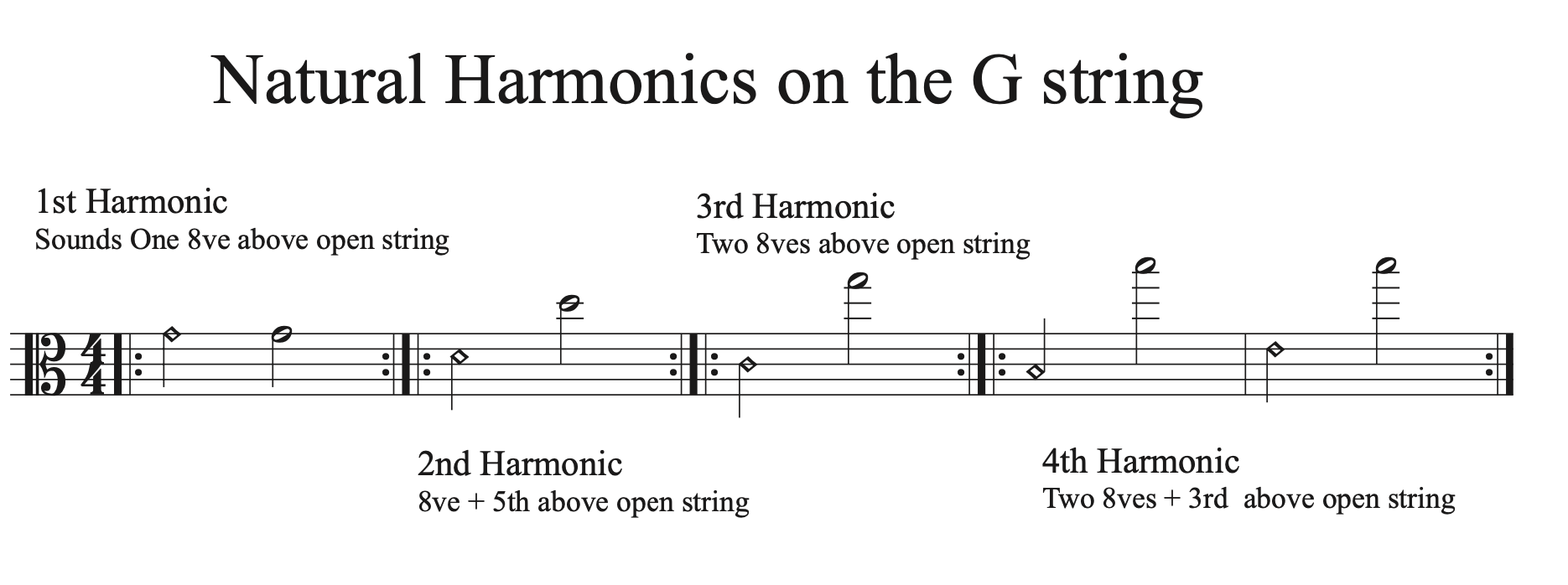

There is a convenient cluster of natural harmonics (also referred to as “partials”) in second position on any string where you can practice with all four fingers without shifting. On the G string, these notes fall under the pitches B-C-D-E.

Here are those harmonics along with their resulting sounds (I’ve also included the 1st harmonic for reference):

If they’re unfamiliar to you, take some time just getting used to playing these harmonics and getting a ringing sound.

Ensure you’re putting some of your awareness on your bow as you practice them! In particular, as your left hand lightens to play the harmonics, make sure the bow is playing into the string. While we’re training the patting of your head (assuming you pat with your left hand!) we want to make sure the rubbing of the belly doesn’t go haywire! On the bow side of things, harmonics generally like a faster bow speed and a contact point closer to the bridge.

This little ditty, called "The Spirit Bugler" in its slow incarnation and "Distant Fife and Drum" in its faster one, from Paul Rolland and Stanley Fletcher's "New Tunes for Strings" is a simple and fun piece in harmonics. It uses just the 2nd and 3rd partials.

In the video below I’m playing in 3rd position on the G and D strings, starting with my 1st finger on C. (The tune can also be played in first position with fingers 3 & 4, second position with 2 & 3 and on any pair of adjacent strings.)

While harmonics are great for developing a lighter left hand, in performance I would often find myself tightening the hand. How can we train the hand not just to play lighter, but to learn how to release tension?

The "light touch" exercises in Hans Jensen and Minna Chung's book "CelloMind" taught my hand this critical skill. (Jensen is also a co-author of "PracticeMind"). I had practiced minimum pressure exercises for the left hand since coming across them in Simon Fischer's books, then later with Nathan Cole's great MVP video, but somehow these exercises clicked with me in a deeper way, perhaps because I just found them fun!

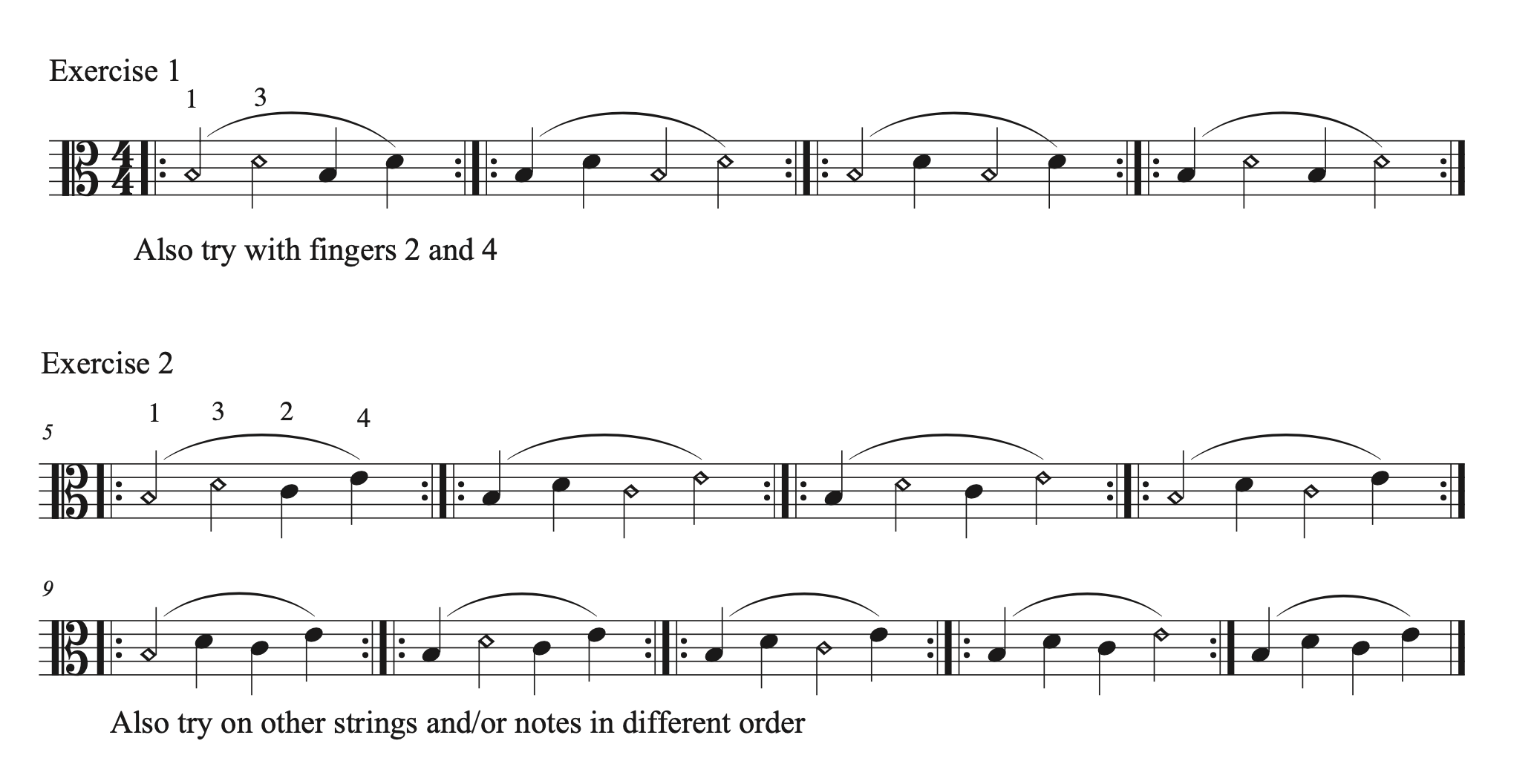

The basic premise of the light touch exercises is to alternate between harmonic and regular pressure. By switching frequently between these settings, the hand adopts a lighter overall pressure, but, perhaps more importantly, regular practice trains the the hand to be able to release tension at any moment.

Here’s my own version of these light touch exercises, played on the G string, starting on the harmonic under B. In this notation, all the diamond head notes are played with harmonic pressure, the solid notes are played with the least amount of left hand pressure needed to get the notes to speak clearly.

Light Touch Exercises

For both exercises, repeat each measure until the harmonics speak clearly and easily. Remember to lift fingers that aren’t playing and ensure the bow is playing forte!

After playing through the exercises, try playing a short phrase or scale. How does your hand feel? Lighter? Springier? More youthful?

As a result of these light touch exercises, now when I feel tension creeping in I'm confident that I can release it (or at least some of it!) quickly. This skill, along with the plop, has become such a critical part of my left-hand technique that I revisit it a few times per week. And since left hand tension tends to rear its ugly head even more in performance, I always dedicate time to this skill in my performance warmup.

In addition to these exercises, you can incorporate "light touch" exercises into passagework, alternating harmonic pressure with stopped notes, either at fixed intervals (e.g. every measure, every four notes) or to keep your hand "on its toes" practice throwing them in randomly.

Harmonics are great for learning to modulate the pressure in the left hand while keeping the bow into the string, let's look at a similar exercise for the right hand: ponticello.

Ponticello — A bridge to effortless Tone

Years ago I watched this wonderful masterclass with Donald Weilerstein, violinist of the Cleveland Quartet and faculty at the New England Conservatory. The whole class is great, but this part on ponticello really got my wheels turning.

Ponticello for those unfamiliar, is the Italian word for "bridge." Pre-19th century composers occasionally direct us to play sul ponticello, meaning "at the bridge" for the icy tone it creates, while 20th and 21st century composers employ all kinds of variations of ponticello to explore the various colors (from glassy to shrieking!) that come from the high overtones of the string. (Here's a brief intro on overtones, and here's a cool site for going deeper into the science of overtones.)

Weilerstein has the quartet play a passage ponticello, then "half ponticello," and finally "1/64th ponticello." (Obviously no one could measure 1/64 ponticello, this is simply a reminder to ride the edge of the ponticello feeling while playing!) At the end of this experiment, the quartet is making a gorgeous tone. What's going on here???

I tried this exercise myself on a passage, moving from the icy ponticello sound to a "normal" sound. I loved the tone I got at the end of the experiment, but was blown away by the ease with which I was drawing the sound. I started to think about what it means to play ponticello, and why moving from ponticello to a normal sound made my sound production feel so effortless.

During the ponticello experiment, Weilerstein advises the quartet to "feel the rub" of the string, so that the sound is “deep even though it's soft”. In essence, ponticello sensitizes the player to the friction between the bow and the string, the force at the root of how we make sound. By starting with the least amount of pressure necessary to produce a consistent friction with the string, then gradually increasing the pressure and moving away from the bridge, we learn the most effortless way to get a deep sound!

Put another way, by playing a passage ponticello, and then less ponticello, we are in essence performing a minimum pressure exercise for the bow, moving from not enough pressure to just enough to get the string to resonate fully. Circling back to our opening metaphor, playing a fingered passage ponticello is akin to rubbing your belly with greater or less weight, while you pat your head lightly.

Getting Started with Ponticello

Open Strings

Practice an open string ponticello. Play with a slow bow near the bridge, focusing on a deep friction (“rub the string” ) with the bow. You shouldn’t need very much weight to get the sound. The tone should be soft but deep.

Next, try 1/2 ponticello. Playing near the bridge generates the most partials in the sound, but you can get a ponticello sound (what Simon Fischer calls "the high scratch") by playing at any contact point with too little pressure or too fast a speed (or both). Weilerstein doesn’t specify what he means by 1/2 ponticello — my instinct was to move slightly further away from the bridge and use slightly more pressure.

Finally try 1/64 ponticello. In this step, I imagine that I’m riding right on the edge between a fully resonating sound and slightly too light a pressure to get that resonance. It’s as if at any moment I could slip into the ponticello color.

Scales

When you feel comfortable on an open string, practice a scale the in same way as you did the open string, moving from full ponticello to 1/2 ponticello to just a whiff of ponticello. Just as the bow likes to come out of the string when the left hand lightens for harmonics, the left hand likes to lighten excessively when playing ponticello, so be sure to reserve awareness that the left hand is fully stopping the string and otherwise behaving itself. In my own practice with ponticello, I’ve found my vibrato likes to get slow and lazy!

In a Passage

This is where the benefits of ponticello shine. Here’s a video demonstration of what the process might sound like on the opening of the 2nd Movement of Mozart’s Sinfonia Concertante, which I renamed Sinfonia Pont-certante (sorry, not sorry).

Harmonics & Ponticello: Partially Perfect in Every Way

Practicing these two techniques will lead to a higher level of individual control over your hands, increasing your level of coordination, but there are so many extra benefits! By getting comfortable playing near the bridge you develop a deep, rich and complex sound. Using the minimum pressure needed in both the left and right hands, you’ll reduce tension in both arms, developing greater ease and fluency in your playing. This will likely be much more impressive than your virtuoso skills at patting your head and rubbing your belly!