Practice Passagework like Primrose

In high school I got my hands on a copy of David Dalton's wonderful book "Playing the Viola: Conversations with William Primrose." (Thanks, Mom!)

Sadly out of print (and ridiculously expensive on Amazon) this book of viola lore details Primrose’s journey with the instrument and his insights into playing, practicing and teaching. But more than anything else, it paints a picture of the unique and vivacious character that was Primrose: a man of great wit, iron discipline, and some memorable turns of phrase. (One of many favorites from the book: when asked if all violinists should be forced to learn viola he responds, “Well, it purifies their souls.”)

Growing up on the outskirts of a small college town in Oklahoma, I was a bit starved for high-level viola resources. I DEVOURED the book, trying out many of Primrose’s ideas along the way. As a teenager I remember being particularly struck by this passage from the chapter "On Practicing":

“(I came to) the realization that security might be achieved by repetition, and being a person of some methodicalness, I arrived at sixty repetitions as being an adequate number, hence my ‘rule of sixty’...As it turned out, it proved to be timely whether I practiced a bowing pattern or was engaged in a left-hand problem. However, I soon became aware that in repeating, I might easily become confused as to the number of times I had indeed repeated a passage unless I marked each off in some fashion. How better than to resort to bowing variants, and thereby organize the confusion? In resorting to an arbitrary series of bowing patterns, I perceived that this would give me bowing practice combined with left hand practice, an economy that immediately appealed to my Scottish instinct!”

Primrose goes on to describe how each variation should be practiced six times — at the frog, middle and tip, starting both down and up bow. (10 variations) x (3 parts of the bow) x (2 bowing directions) = 60 repetitions.

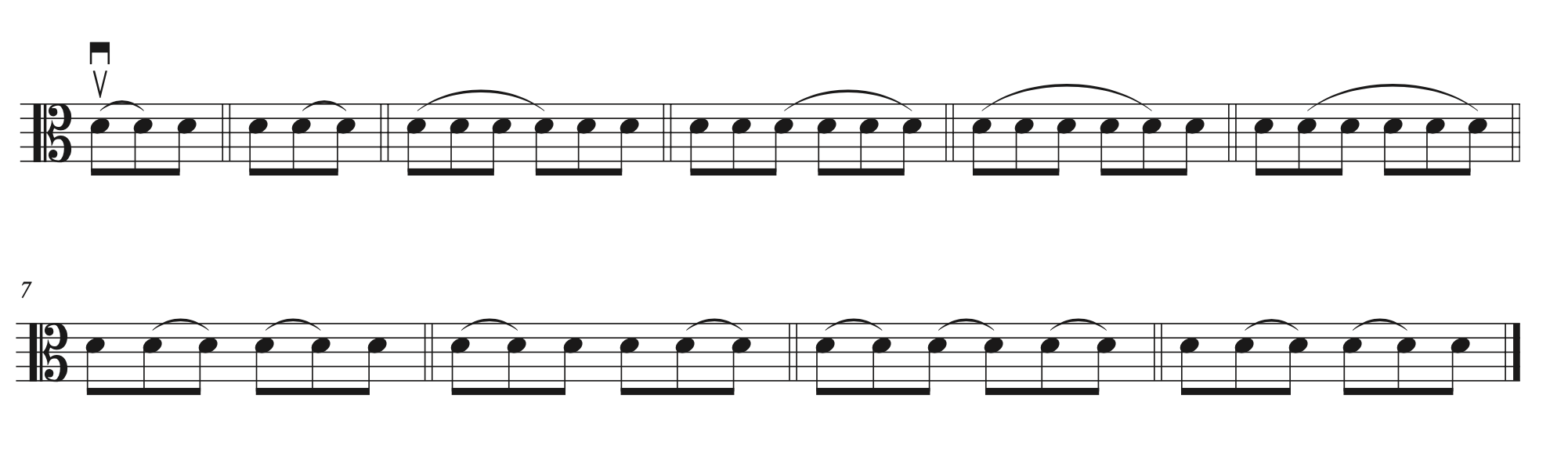

Here are the variations for passages that have notes in groups of four:

And here for groups of passages with notes in groups of three:

High school Travis read this passage and had two thoughts: "Whoa, this dude is intense!" followed quickly by "I want to try that!"

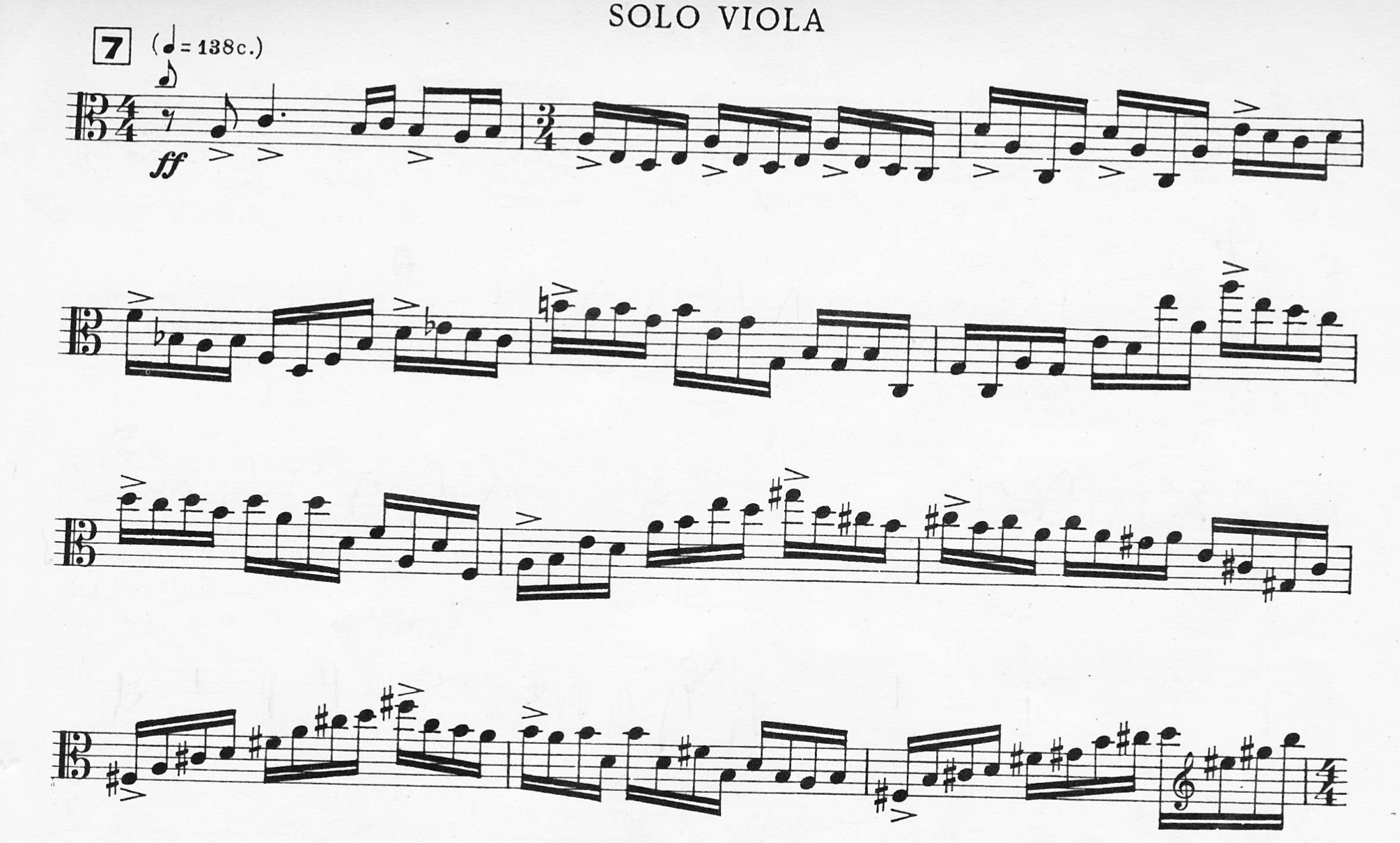

I chose a tricky passage from the first movement of the Walton Concerto as my test subject for Primrose's prescription. This section had eluded me for months, so I figured it was as good a choice as any.

After playing it through with all 60 variations, I played it again normally. Right away I noticed a few things:

My bow arm felt amazing! There was a newfound ease, balance and fluidity to my whole right arm.

Improved coordination. The timing between my hands had improved immensely! Since the left hand has to articulate more in slurs and the right hand more in separate bows, the variation of separate, slurred and mixed bowings forces the hands to solve a number of coordination puzzles.

I had memorized the passage. Small wonder, given how many times I played it!

I was mentally exhausted! No surprise here, either. This work requires a ridiculous amount of concentration! By about twenty repetitions or so I was beat; the rest felt like I was just going through the motions.

A Primrose Prescription for Mortals

My high school foray was the ONLY time I made it through Primrose's practice method as prescribed. Most of us don't have the discipline of Primrose, and frankly, this many repetitions is likely overkill in most situations, not to mention potentially injurious if done mindlessly!

Here are some suggestions to modify Primrose's routine to maintain its benefits, without some of its downsides.

Spread Out the Repetitions

This is something Primrose alludes to further in the chapter but never fleshes out. Instead of one sixty-minute session, which will likely result in a high number of junk repetitions, break the practice up into smaller sessions. For example, if you practice twice a day, aim for a ten-minute session in each of those sessions (or, better yet, two five-minute bursts during different parts of the session).

Two daily sessions of ten minutes over three days adds up to one sixty-minute session, but by spreading out the reps over many sessions, your quality of attention will be higher and each repetition more valuable. Since it takes about three days for things to sink into our long term memory, this plan also ensures a more lasting impact to your practice.

Alternatively, go by feel to determine how many repetitions to do in a particular session using the idea of Minimum Effective Dose: practice with the variations until you begin to lose concentration, or feel the passage stabilize, then stop and move on to something else.

Practice Slowly à la Burton Kaplan

"Practice slowly" is a common refrain, but rarely is a clear definition of "slow" actually given! Do I play everything at 16th note = 60? Or at a certain percentage of my goal tempo?

I LOVE Burton Kaplan's definition of slow practice in "Practicing for Artistic Success," which he defines as a tempo that meets all three of these criteria: “first, you should experience physical ease; second, you should feel calm; and third, you should be able to experience the notes as a musical pattern in slow motion.”

Physically relaxed and mentally engaged is a sweet spot in our concentration — it also describes how I want to feel when I'm performing! Mental and physical states, not just notes, are baked in during practice. Being mindful of those states while practicing is important! If you're tight or stressed while practicing a passage, and repeat it many times with those feelings, your body learns to associate those states with the passage, and will dutifully execute it similarly come performance time.

Play Musically

It's easy to devolve into "etude brain" when practicing with a method like this. “Etude brain” is what I call the kind of robotic, expressionless practice that often occurs when performing a technical exercise.

To circumvent this detrimental state, while playing one of the variations imagine that the composer actually wrote the music with that bowing. Search for the subtly different character that each bowing pattern creates, and exaggerate it! Changing articulations (for example playing the separate notes on or off the string) brings out even more characters, and bowing challenges!

Trying out a different phrase shape on successive variations is also a great way to keep the mind engaged while simultaneously building musically flexibility. Alternatively, if you're feeling musically stale, pick one of the emotions from Karen Tuttle’s list. First sing the passage through with your chosen emotion, then play it through. Sing (and play!) with conviction!

A useful tool in the kit

In my current life I’ve found Primrose’s “Rule of 60” useful when I have a stubborn passage that doesn’t succumb to my regular practice tools. I’ve also used it when I want to memorize a passage, or in the very particular case when I’ve changed a fingering in something I’ve memorized: I know I need many repetitions to “reprogram” the new fingering into the passage, but want to practice in a way that keeps me engaged. At other times I’ll use Primrose’s Prescription simply for a great bowing workout — either on a passage from my repertoire or in an etude like Kreutzer, Mazas or Tartini.

Try it out yourself and let me know what you think!

Update: For those interested in purchasing the book, it’s slightly cheaper electronically through the Google Play store. Thanks to one of my readers for that tip!