James Dunham on Technical and Musical Timing

Last month I had the pleasure of hosting James Dunham in a guest masterclass for my String Gym students. Dunham is Professor of Viola and Chamber Music at Rice University’s Shepherd School of Music, and the former violist of the Cleveland and Sequoia Quartets. He also happens to be one of the nicest people I know!

I studied with James in several contexts while I was a student at Rice, so it was special for me to see my own students work with him. James shared many helpful ideas throughout the class, but there was one nuance of the bow, what he referred to as “anticipation,” that shed light on many aspects of Technical and Musical Timing in my own practice long after the class was over.

What ARE Technical and Musical Timing?

Musical Timing is the moment in chronological time when you want a sound to come out of your instrument. Technical Timing is the moment you have to do something on the instrument before any musical moment in order for the instrument to sound. Pedagogues from Galamian to Fischer talk about the importance of understanding this topic:

“The subject is as important as the principles of tone production, intonation, or of how to hold the violin. Yet compared to these it is a ‘hidden’ subject, often unrecognized, and the results of poor technical timing can be heard even in the performances of otherwise high-level players. ”

Examples of this “hidden” subject are all around us! If I want to play any fingered note on the instrument, for example, my finger has to go down in advance of when I actually draw the bow. (Mimi Zweig’s name for this particular rule of Technical and Musical Timing is “finger before bow”) Now, it may be only milliseconds in advance, but if I don’t put the finger down and fully stop the string before I move the bow (Technical Timing) the instrument won’t speak clearly when I want it to (Musical Timing). Though seemingly obvious, it’s amazing how often we break this rule!

It’s a bit like a conductor leading an orchestra. If a conductor were to show a crescendo exactly when he wants the orchestra to start it, he’ll always be disappointed —the players need time to react! On the other hand, if the conductor begins to make his wild gesticulations for an expressive crescendo slightly ahead of where he wants them, the orchestra has time to respond…assuming they are paying attention!

But there is a bit of paradox when it comes to slow pieces. And that’s what James would illuminate for me.

Slow Tempo, Fast String Crossings

The particular detail of this concept James focused on dealt with the bow, and arose in a student playing the Largo from Telemann’s Fantasia #1. The opening of this movement features a beautiful dialogue between the lower and upper registers of the instrument. This internal conversation requires many string crossings, and the student was having trouble getting those notes to speak clearly on time.

Telemann: Fantasia #1 - Largo

James pointed out that for the notes to sound in time during these constant crossings, the bow has to anticipate the next string level, or as he elaborated later, “the ‘old’ stroke ends at the start of the ‘new’ stroke, in preparation.”

In my own practice I found that in spite of the tempo being slow, the string crossings themselves had to be faster than I expected. I had thought that the slow tempo afforded me MORE time to cross strings! But especially because of the skipping of strings (C to D in m. 1-3 and G to A in m. 4) involved in this particular example, the bow has to move quickly to the new string to make a seamless connection between notes.

This nuance of technical and musical timing – that the speed of our movements doesn’t always match the tempo of what we’re playing – hadn’t REALLY clicked for me before. I’d registered it to a certain degree on the left hand side of things (see my previous note on “finger before bow”), but I’d never understood this aspect of timing fully on the bow side of the equation.

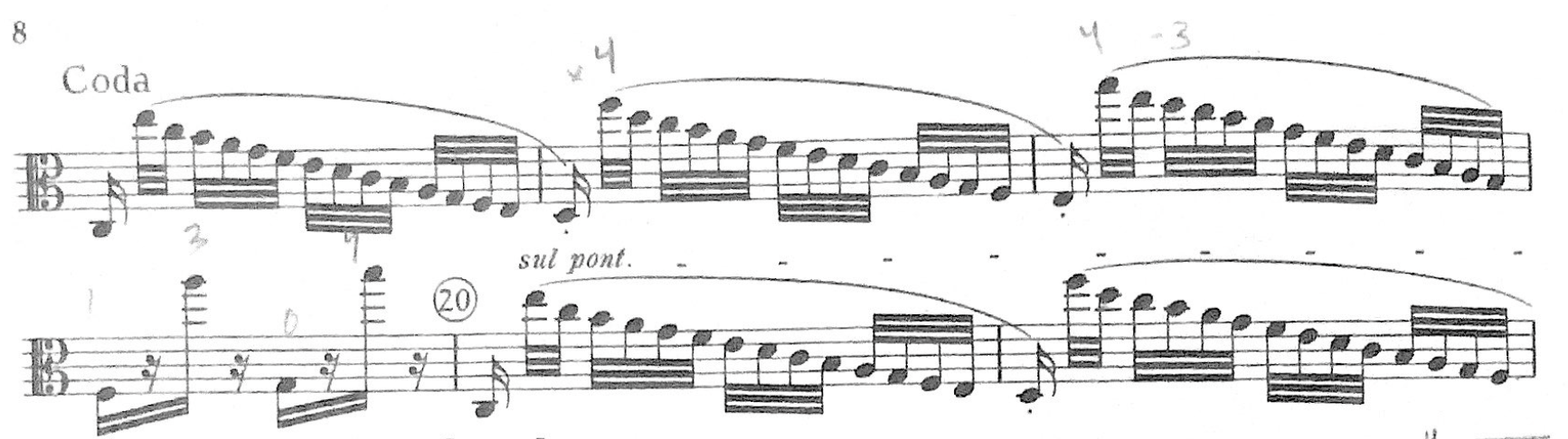

Nathan Cole, my own coach, shared a similar observation about very quick motions of the bow and fingers in the string crossings that happen at the beginnings of each measure in this passage from the Paganini Sonata:

Paganini: Sonata for the Grand Viola and Orchestra - Coda

But since the tempo of this piece is fast, I’d never truly made the connection that this could be the same for slower pieces as well! To get the concept through my thick skull I needed another voice to frame the idea in a slightly different way.

Side note: This is also why I love having masterclasses for my own students! Guests often works on familiar concepts, but because she frames it differently (and it’s not me saying it) the idea hits home for the student. My favorite is when the student comes to me afterwards saying, “Travis, did you know that I should be doing [insert technical/musical idea we’ve been working on for months]?”

I’ve learned to smile and nod.

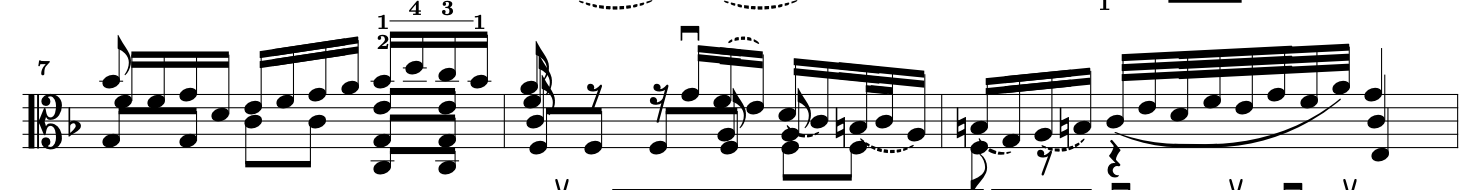

Back in the class, James showed how he uses Kreutzer #7 to work on this idea, training the bow to anticipate the next string level.

Kreutzer #7

He demonstrated how you could practice the etude ending each bow ALREADY ON THE STRING LEVEL OF THE NEXT NOTE. In my own practice I found this makes the string crossing very quick, no matter the tempo! It also trains the player to integrate the technical timing needed when playing faster, but the player has more time BETWEEN notes to think about and prepare the next action.

I realized a similar approach could be adapted to “etude-ize” the numerous crossings in the Telemann Fantasia.

Telemann in the style of Kreutzer 7

As often happens, as soon as I was aware of this technical issue it felt like I saw it everywhere!

Here’s a similar lyrical example from the section soli in the first movement of Shostakovich’s Symphony #5:

Shostakovich Symphony #5

Though the note values are quite long, the string crossings themselves have to be quick! This is especially an issue if the player uses the common fingering of starting on the G string for the first F#.

In the Andante from Bach’s Solo Violin Sonata #2 we can see how this problem affects chordal playing. In this example from measure 7, the bow has to cross strings VERY quickly for the 4-note chords — first to get from the D string at the end of the 2nd beat to the C/G strings on the 3rd beat, and then AGAIN two notes later from the D on the A string to the C/G on the “and” of beat 3.

Bach Solo Sonata #2 - Andante

Of course this problem isn’t just limited to lyrical or slower music – the same issue with the bow needing to move very quickly to cross (or often skip over) strings happens all the time in faster excerpts.

In addition to the Coda from the Paganini Sonata for the Grand Viola, I also found this practice method extremely helpful in Variation 1 of that same piece:

Paganini - Sonata - Variation 1

Mozart Symphony 35 presents numerous chances to deploy this skill - right in the opening phrase, and throughout the movement!

Mozart #35: Mvmt I Excerpt

Crossing over

There are a seemingly endless number of things about playing a string instrument that are nonintuitive. In my studio the running joke is: “This is annoying thing #3251 about playing the viola.” The more I learn about the instrument the larger that number seems to get! For me, the timing of string crossings was one of those nonobvious concepts. I’m grateful to James Dunham for shining a light on this issue (and its solution!), which connected many other puzzle pieces in my own head about Technical and Musical Timing as a whole.